In the midst of planning a book project, you might find yourself daydreaming about what the end result will look like (especially when you’re tired of writing and need a pick-me-up!). There’s a special kind of pleasure in imagining how your favorite photographs will illustrate the text and the cover. For a family history, you might be thinking of the prized sepia-toned studio shots of stiffly posed great-grandparents, and, for a memoir, the beloved baby pictures and weirdly colored Polaroids from the ’80s.

But before you tear that stack of albums apart, let’s pause for a moment and consider why you’re choosing the photos you’re choosing. And then we’ll show you a system for streamlining the process.

It’s not difficult, but it is a little counterintuitive. Because in order to work efficiently, you need to start with the book’s manuscript, not those plastic-coated pages you’ve been dying to tear into.

Get Organized

Step 1:

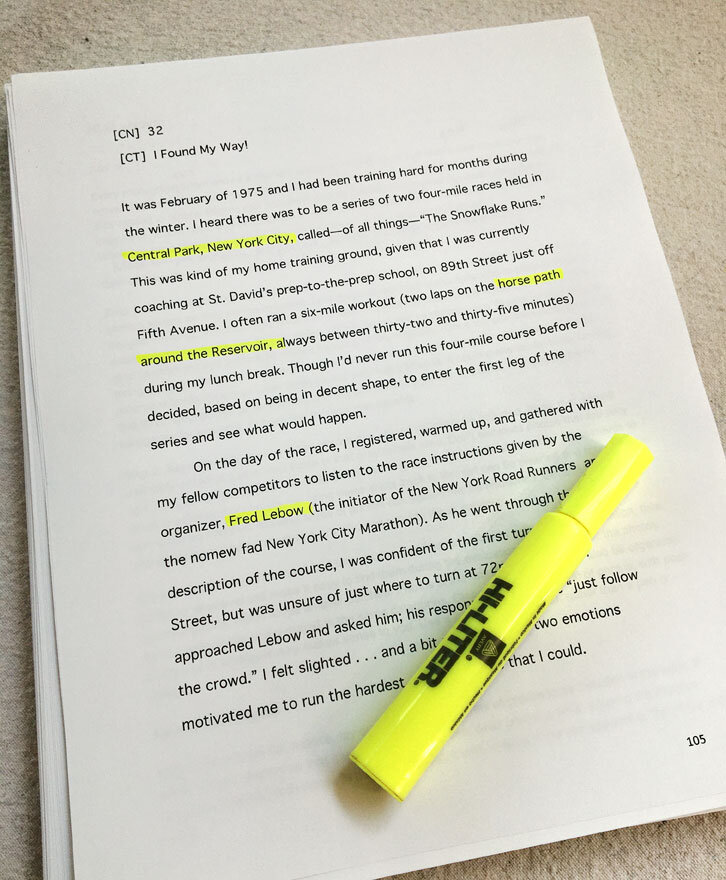

Skim the book’s manuscript and highlight places in the text that would be enhanced by an image. This is the time to think big: Don’t worry about whether you actually have any of these images! Imagine that you’re the reader. At what points in your reading would you ideally come upon an image that helped you understand and visualize the people, places, time periods, and cultures that you’re reading about?

To ensure your memoir or family history tells a cohesive story, start by reviewing the manuscript—rather than your photo collection—for image ideas.

Step 2:

From those highlighted phrases, compile a list of images that would support and enhance the text. Photographs of people are an obvious choice. But don’t neglect places (houses, neighborhoods, or maps), pets, important objects (like collectibles or wartime medals), and even ephemera like letters and ticket stubs.

Step 3:

From that list, collect all photographs that would be appropriate for your project. For each one, note the photo’s source, so that it can be returned easily. Look beyond your own photo collection for special images—original photos, high resolution scans, or documents—that family members, friends, or even archives might have on hand.

Step 4:

Now comes the review stage: Make copies of photos that exist in digital form or as slides. Using a laser printer is fine for this purpose. (Check out the smartphone app SlideScan, which converts slides to digital images.) To reduce the handling of fragile photos, shoot each with a smartphone and make laser copies. (Once the selection process is over, consider using a scanning service to ensure high-quality images.)

Step 5:

Revisit the process for more themes. For an extensive family history or large project with many images, it could make sense to go through this process more than once, focusing on paternal, maternal, and descendants categories, for example, to keep this stage of the project manageable.

Adjusting settings and levels within a photo editing program can make the difference between a so-so image and one worth using.

Step 6:

Create batches of photos: those that should definitely be included, those that should definitely not be included, and those that you’re unsure about. Don’t eliminate important photos that are very light or dark, muddy (with all tones as shades of gray), or dirty, or those marred with white spots or scratches. Adjustments to black-and-white or color levels can bring these shots back to life; dirt can be cleaned, and tone in white spots and scratches can be restored. Missing areas of photos can sometimes be retouched.

Assess Your Photos

Step 7:

Review the photos in the DEFINITE batch against the list of preferred shots compiled in Step 2. Check off those list entries for which you have photos.

Step 8:

Divide the photos you intend to use into smaller batches, grouping by subject matter, location, time period, or any other useful category. Order the photos chronologically within each category. Photos in the UNSURE batch should also be grouped using the same categories and organized chronologically. Label each batch of photos (Post-It notes are ideal), and always use a pencil with soft lead, rather than a pen or marker.

Step 9:

On a large flat surface, lay out the smaller batches of photos to be included in the book. If space allows, display so that each photo can be seen, even partially, while keeping the batches separate. Review each image in the UNSURE batch against the STILL-TO-FIND entries on the compilation list. Then review each UNSURE image with others in the DEFINITE category. Eliminate images that don’t contribute to the text or that are too similar to shots already slated for use.

Step 10:

Ideally, the number of photos in the UNSURE batch will now be a manageable size, and each can be evaluated more thoughtfully. Here are some questions to help you decide whether to use these photos:

Does the photo capture a unique person or facial expression?

Does it offer hints as to how people lived—vintage photos taken in kitchens can be a goldmine in this respect—or provide a deeper understanding of the subject’s interests or life?

Does it show people relating in a way that the reader might appreciate or find insightful?

Does it draw you in? Do you wish you knew what happened right before or after the shot was taken?

Does it convey something about the relationship between the photographer and the subject?

Ideally, the selected images, across all categories, should be varied. And remember, captions (which will be written at a later stage) are more interesting when they add new information, rather than repeating what’s already obvious in the photo.

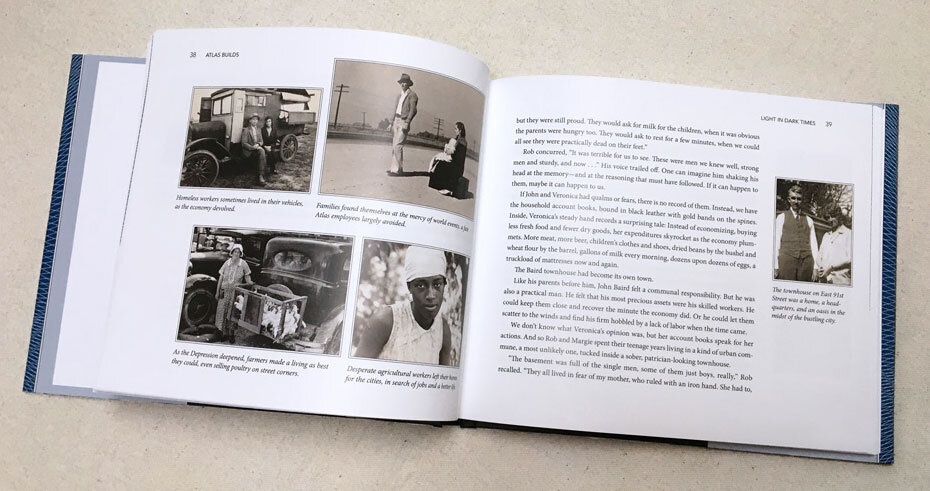

Photos from another era or culture can convey, succinctly, what life was like at the time. In this photo from the early 1900s, a young woman's mother acts as a chaperone during her courtship.

Photos that show people connecting, with each other or the person behind the camera, often make the strongest images.

Think Beyond Photos

The manuscript will really come to life if you can include documents like wedding licenses, certificates, contracts, land deeds, diplomas, and census records; birth announcements; letters and postcards; recipes; report cards; significant receipts, ticket stubs, holiday cards; dance cards; telegrams; and handwritten poems. I remember fondly one terrific layout that included a napkin with a handwritten phone number! The list can also include flat-ish objects such as brochures, military medals, dogtags, jewelry, and the covers of diaries and books. If an important object can't be scanned, it can always be photographed. Just keep in mind that each image should relate to the text.

Choosing images for a memoir, family history, business history—or really any kind of real-life writing—is a combination of art and craft, inspiration and practicality. If chosen, organized, and handled with care, they will add beauty and understanding to the text and help immerse readers in your personal history.

Susan Hood is a veteran book designer and co-founder of Manhattan–based Remarkable Life Memoirs.