The form a memoir takes can be as unique as its subject. While it’s usually a narrative composed of personal experiences, there are other ways to convey the essence of one’s life. As a professional book designer, I’ve employed my skills to preserve my own family’s history in a variety of ways using little or no original text.

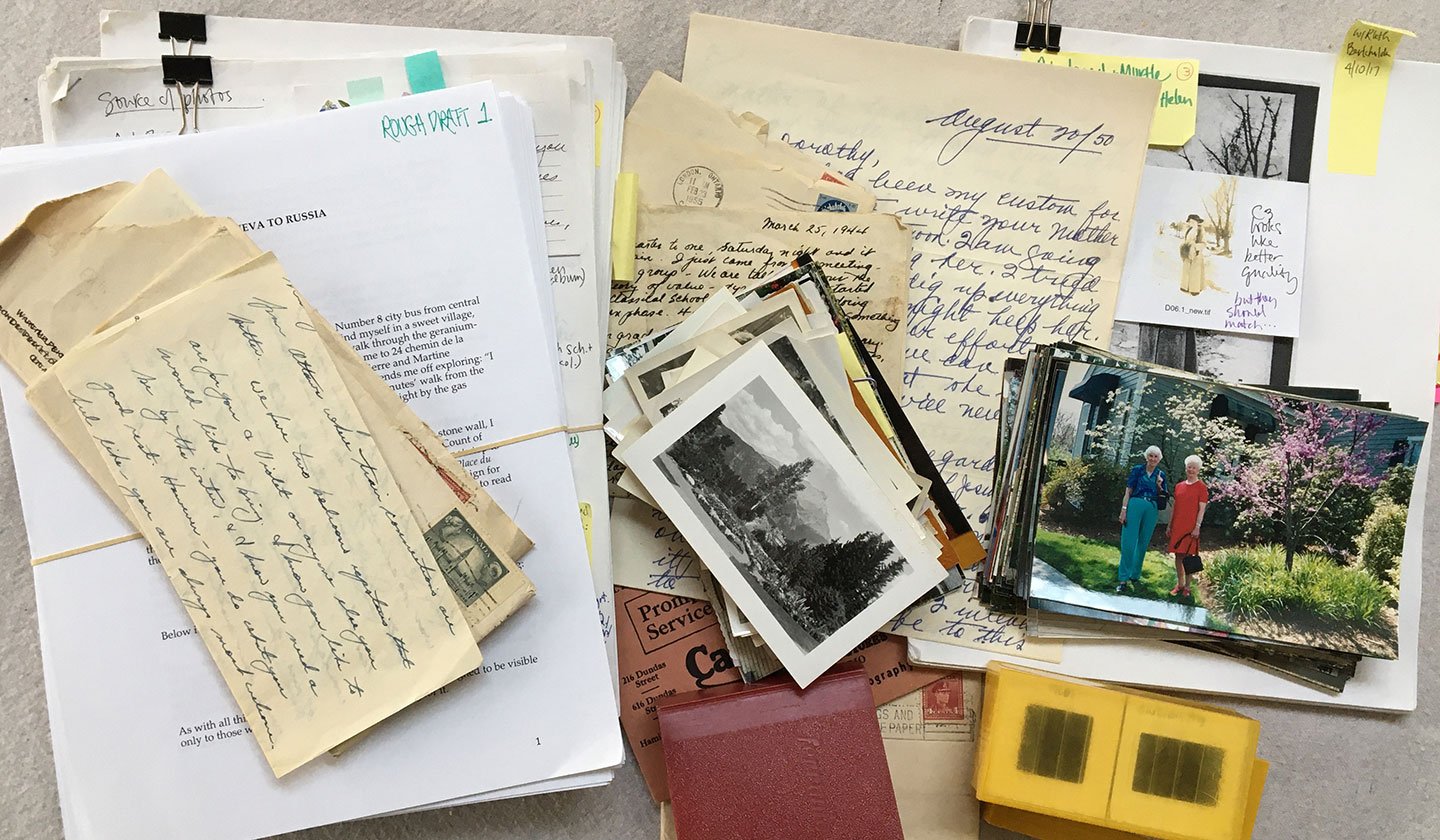

If you have photos, letters, or documents but, like me, not a writer’s ability to craft a story, what are your options? They vary, depending on the type and amount of material you have to draw from.

Your collection includes a large number of photos, letters, and documents

How to know where to begin, when there are so many different directions your project could go in?

Should your book be structured around a significant period of time or event? Should it include previous generations? At what points should it begin and end? The topic of the book should be the story you want to tell, not determined by the images available.

After you’ve decided on the book’s subject, scope, and an approach, evaluate which of your photos and documents could best tell the story. Then, working chronologically, write captions for each image, consisting of the names of people depicted, place, and approximate date. If an image prompts a story or specific memory, include those details too. Remember that captions don’t always need to appear in small print below the images. Elevate their importance by making them larger and positioning them alongside their corresponding images or—if the book is small, on the opposite page.

If you have a large number of photos and documents chronicling your life, a compelling story can be told by producing a large-format book, showing the images in chronological order, one per page, with no captions or text at all. Images at this size should be easy to view and more engaging.

If you have correspondence spanning years, tell the story of the relationship by displaying the letters on individual pages. In cases where the handwriting is particularly hard to decipher, transcriptions could appear below or opposite each letter’s page.

This memoir of my father’s life consists entirely of images. In addition to his birth announcement and draft notice, are his wedding ring receipt, hospital bills for his children’s births, and Bob & Ray Fan Club card.

A smaller and more traditional book preserves some of the photos, stories, and poems from my mother’s life.

You have some photos and documents, but not a lot

Supplement what you do have by looking beyond what’s typically used to tell a life story.

Before committing to a project using only what you have on hand, look further. Do you or family members have letters, old journals, calendars, family recipes, or anything else that might help tell your story? Ask the open-ended question and you may be surprised by discovering something of real significance.

Facts, impressions, and stories transcribed from recorded interviews with family members can be the basis of a rich family memoir. Add the source for each memory and reorder them by categories. These categories can then become separate chapters in your book.

If the subject of your book is ancestors in one of more branches of your family tree, use online genealogy websites to search for documents such as: federal, state and agricultural censuses; birth, marriage, death, and military records; deeds; wills; and burial sites. These documents can be a gold mine of interesting facts and details. In addition to showing the documents at a readable size, the information they provide could be summarized in bulleted lists, essentially serving as biographical family sketches. (Transcribing a document could be an option if the handwriting is hard to read.)

If your personal or family memoir stretches back generations, books in the public domain such as 19th century local histories and county atlases are resources that can provide depth and context on the area and time period in which your family lived.

A pandemic project about my grandparents grew in size and scope to include many documents, maps, and photos relating to our ancestors.

You have no photos, letters, or documents at all

Think beyond what you might consider a typical document.

What do you have that reflects who you are and what you want to remember?

Let email correspondence tell a noteworthy story. Whether it’s an account of an adventure, the development of a romantic relationship, or the birth of a child, showing images (screenshots) of each email at a size that’s readable allows the reader to become engrossed in the experience.

If you have a decades-old diary, scan and show each page on its own book page. Captions can consist of contemporary comments, reactions, and insights.

Create a recipe book of favorite foods. Show photos of the actual recipes and include shots of well-loved kitchen accoutrements such as patterned dish towels, pot holders, quirky implements, or vintage appliances.

Do you or family members have possessions with extra significance, whether little mementos or valuable heirlooms? Create a small photo book of these objects, each with a brief caption noting the item’s importance along with a family member’s memory of it.

Think completely outside the box and create a one-of-a-kind handmade book. Some examples: Bind similarly-sized grade school artwork; photos chronicling your needlework hobby, sewed to fabric pages; or a decade of calendar pages with its handwritten notes detailing how days were spent. Consider how any object that reveals your essence or interesting details about your life could be preserved in book form.

The Hood recipe book preserves well-loved recipes for four appetizers, eight side dishes, 12 main dishes, and 47 desserts.

Final suggestions

Determine the scope of the project before starting. Are you up for creating an in-depth book which would likely take years to complete? Would putting together a short book about yourself or a significant person, time, or place be a more realistic project? Maybe something in between? Deciding this at the beginning of the process will help in working efficiently and in staying focused on your overall plan.

Add book features such as a title page, chapter titles, and page numbers to help organize your story and give your book a more polished appearance.

Consider how the book’s format (softcover, hardcover, clothbound, or leather-bound); size; orientation (portrait or landscape); and the addition of extras, such as a family tree or illustrated map can enhance your story.

Lastly, if you’re producing a family memoir and have talented relatives who enjoy writing . . . delegate!

Susan Hood is a veteran book designer and co-founder of Manhattan–based Remarkable Life Memoirs.